2010 – Ennedi Desert, Chad

Details

Team: Mark Synnott, Alex Honnold, James Pearson, Jimmy Chin, Renan Ozturk, Tim Kemple

When: Nov.13-Dec.3, 2010

Where: Ennedi Desert, Chad, Africa

Sponsor: The North Face, Sterling Ropes, La Sportiva, Petzl, Metolius, Clif Bar

Explore Mark's other expeditions:

Trad in Chad

The mysterious towers of the Ennedi

By Mark Synnott

The fin of rock above me, Aloba Arch, was 300 feet wide, 50 feet thick, and stretched all the way across the canyon 700 feet above our heads. Alex Honnold and I were discussing a possible route to its untouched summit when I noticed four young men emerge from the rocks in the back of the canyon. Clad in sandals, with scarves partly covering their faces, they wore large knives in their belts and were holding the hilts with one hand as they purposefully strode towards us.

Moments later they began shouting at us in Arabic and gesticulating wildly. I had no idea what they were saying. “Let’s get the hell out of here,” I yelled to the rest of our team, which included Jimmy Chin, Tim Kemple, Renan Ozturk, and James Pearson. We beelined through the sand toward our gear, stashed at the entrance to the canyon, but the assailants fanned out around us. One grabbed Renan’s pack, which was filled with about $10,000 worth of camera gear. When I arrived the guy had one hand on the pack and the other on his knife, but Renan also had a hold on the pack and, with a violent jerk, tore it from the guy’s hands—which seemed to really piss him off. Yelling, he unsheathed his knife and began lunging at Renan, while pounding his other fist into his chest.

My instinct was to run, but as I turned around I saw Jimmy pick up a softball-size rock. “Holy Crap,” I thought, “Chin thinks he’s a caveman.” I looked down at my feet and spotted a gnarled tree branch, and the next thing I knew I was standing next to Jimmy, assuming the “batter-up” position. If Chin was going Cro-Magnon, then so was I.

LINESPACE

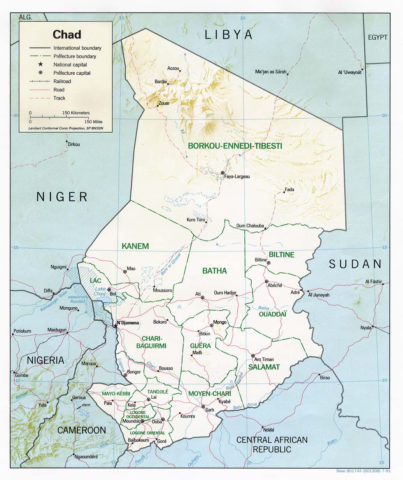

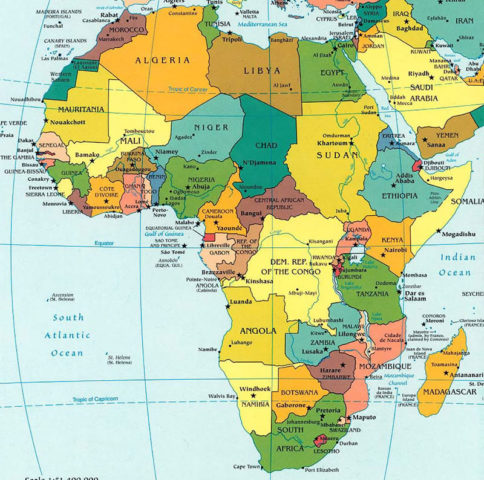

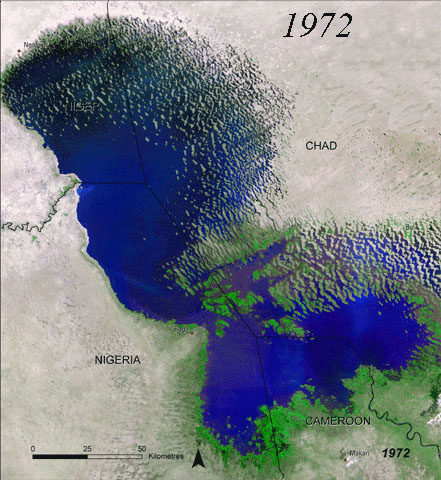

The Republic of Chad, an arid, impoverished, landlocked country, is often referred to as the “dead heart of Africa.” It borders Libya to the north; Niger, Cameroon, and Nigeria to the west; the Central African Republic to the south; and Sudan to the east. It is named after Lake Chad, on its southwest border, which is Africa’s second largest body of fresh water. Unfortunately, the magnificent lake, which supplies water to about 20 million people, is slowly drying up. A United Nations report states that it shrunk by 95 percent from 1963 to 1998, although it has rebounded somewhat in recent years.

A former French colony, Chad gained independence in 1960, but has been ravaged by conflicts, and since 2005 has been engulfed in civil war. In 2008, rebels opposed to the presidency of Idriss Deby stormed the capital of N’Djamena and took over a large part of the city. Hundreds of people were killed before the coup attempt failed and the rebels retreated into the desert. Since 2003, Chad has been further destabilized by the Darfur Crisis in Sudan. Hundreds of thousands of refugees have spilled over the border and are living in camps along the eastern border, not far from the Ennedi Desert. A similar situation exists on the north, due to the conflict in Libya, and on the south border with Central African Republic. According to the US State Department, the average life expectancy in Chad is 39 years.

I first became aware that Chad might have potential for unexplored rock climbing in 1999 during an expedition to the Mandara Mountains in Cameroon. I knew that climbers had visited the Tibesti Mountains in northern Chad, but I wondered if there might be anywhere else. So I took a look at satellite pictures on Google Earth and that’s how I found the Ennedi Desert, a 60,000 square kilometer area of canyonlands near Chad’s eastern border with Sudan.

Like a lot of sponsored expeditions, our team was split into two contingents, a climbing team and a media team. For the latter we had the Camp Four Collective, a new video production company made up of Chin, Ozturk, and Kemple. The climbing team was myself, Honnold, and Pearson. Most readers of this magazine are familiar with Honnold, who has become a household name with his free solos of routes like Moonlight Buttress, the Northwest Face of Half Dome, and Red Rock’s Rainbow Wall.

James Pearson is not as well known in the US, but in some ways is kind of the British counterpart to Honnold. He first made a name for himself in 2005, at age 19, with a fast repeat of the infamous Equilibrium (E10), a gritstone arête that at the time was considered the hardest traditional route in the world. Three years later, Pearson proved it wasn’t a fluke when he solved one of the UKs last great rock-climbing problems, notably called “impossible” by some of the world’s best gritstone climbers: The Groove (also E10) at Cratcliffe Tor.

I barely knew him, but Pearson proved to be funny and easy going. I’d end up learning a lot from watching him climb, and even more from his theories about women and dating, which kept us entertained for hours in the jeeps.

The six of us arrived in N’Djamena in mid November and set off the next day in two Toyota Land Cruisers and a Land Rover with our outfitter, a 66-year-old Italian named Piero Ravà. Piero—a true character, complete with tweed cap and a pipe permanently stuck between his teeth—first visited the Ennedi in the early 1990s, and began quietly taking European adventure tourists on photo safaris there. He assured us that we would be the first group of climbers to visit the area.

We had been traveling Chad’s only paved road for less than an hour when Piero suddenly veered off into the sand. I assumed we were stopping, but Piero just pointed the vehicle northeast and kept going—for the next four days.

Sometimes we followed rutted tracks in the sand, while other times it seemed like we were driving across areas that had never seen a vehicle. In the softer sand, the only way we could maintain headway was to drive at 60 mph, with the vehicle skimming precariously at the limit of control. When we stopped to camp at night, our Chadian mechanic would work on the vehicles, cleaning out air filters and sometimes replacing or repairing various engine parts.

We put in long, grueling days of four wheeling, sometimes going from sunup to sundown seeing nothing but flat sand. The key was to spend as much time as possible in Piero’s lead vehicle, because in the following vehicles you lived in a cloud of dust, which worked its way into every orifice of your body. It was the beginning of the Chadian winter, and the temperature hovered in the 90s during the day. In summer, Piero explained, it got up to 140 F.

What amazed me was not that places this desolate exist, but that people lived there and somehow managed to eke out an existence. Thousands of years ago, the Chadian Basin was a massive savannah with trees and rivers. It was an ideal place for nomadic herders raising camels, goats, and donkeys, but as the centuries went by, the rivers dried up and the surrounding desert advanced.

Yet the people stayed. Every hour or so we’d pass a thatched or mud hut, and we’d often see small families huddled in the tiny patch of shade thrown by the dwelling. Chad has more than 200 different ethnic groups, but most of the nomadic people in the north are called Toubous. The Toubous are not accustomed to seeing outsiders and Piero warned against approaching them or taking their picture.

Watering their animals meant repeated trips to ancient wells spaced periodically across the desert, and it was here that we interacted with the nomads. Water bags—made from truck inner tubes with rims woven around saplings or rebar—would be lowered 20 to 80 feet down the wells to the water, then pulled up hand over hand. It was tedious, backbreaking work shared by the entire family, who spent a good chunk of their lives at these wells. Sometimes they would hook the rope to a donkey to do the pulling. Often there would be metal bins on the ground nearby, which they’d fill with water for their animals, and with dozens of donkeys, camels, and goats jockeying for position, a wide radius around the well was typically mired in ankle-deep mud and animal feces. Piero and his crew were purifying the water, but apparently whatever they were using wasn’t strong enough, because most of us were experiencing severe intestinal distress.

On the afternoon of our fourth day we spotted some rock formations in the distance—the first hills of any kind we’d seen since leaving N’Djamena. As the jeeps finally entered the canyonlands of the Ennedi, one thought possessed us: would the rock be any good?

Piero pulled us into the shade behind one of the formations and we literally ran to grab the rock. Seconds later I was bouldering on a solid layer of patina peppered with perfectly incut holds. Even Honnold, who is slow to heap praise on a climb—or anything for that matter—admitted, “Wow, it’s better than I expected.”

A mile or two away there was a concentration of a dozen towers that rose from a small plateau. Some seemed to defy the laws of physics, with bulbous summits sitting atop crab-eye-like stalks. Several were cleaved with giant windows.

LINESPACE

The next morning we arrived at the base of our first objective, which we named the Citadel. This 200-foot tower was shaped like a giant boxcar standing on end, featuring four distinct aretes, one of which appeared to have decent holds. A rotten overhang guarded the bottom, but sported a crack that looked doable. At mid height, however, was a body-length roof, and here there were no visible cracks for protection.

Pearson, who was brought up climbing on gritstone, admitted that he’d never placed a bolt. I offered to show him how, but he said something to the effect of, “I’ll just head up and see how it goes.” He powered through the initial overhang with ease, and soon was positioned below the roof. Jamming a heel-toe lock into a crusty horizontal, he levered out and managed to loop a cordalette over two baseball-sized chickenheads above the lip. He equalized these, then climbed back under the roof to psyche up.

As I watched this impressive display I heard a noise behind me and saw Honnold emerging, ropeless, from a bombay chimney 40 feet up a nearby tower. Above him rose an overhanging fist crack into which he set some jams, then swung his feet out of the chimney. Flowing like a snake up the rock, he was soon manteling over the lip. He built a small cairn and then down-soloed the tower via an overhanging face. On his way down, he broke off several hand and footholds, and I was barely able to watch. He later admitted that the downclimb had been a little more than he’d bargained for.

As Honnold ran off to solo all of the other nearby towers (he did about six first ascents while we were climbing the Citadel), Pearson pulled the roof, making it look easy. The rock above was covered in a chocolate-brown patina, baked into perfect brownies, with solid niches in between into which Pearson stuffed nuts and cams. All told, Pearson’s three-hour lead was one of the most masterful bits of on-sight trad climbing I’ve ever seen.

The tower was breathtakingly beautiful, and just being there climbing it was the culmination of a dream I’d nurtured for more than a decade. I felt a strong kinship with Pearson and huge admiration for the skill it had taken to onsight this tower without bolts. The climbing itself was stunning, and at 5.12a, hard enough that I was glad to be climbing it on toprope.

The summit of the Citadel provided the best view of the Ennedi we’d had so far. Just within a 15-minute jeep ride of our camp, there appeared to be at least 50 worthy towers, and a few that looked downright inspiring. But the Ennedi was huge, and we were barely on the edge of it. Piero wanted to take us deeper, so the next morning we set off again in the jeeps.

As we probed further, it became harder to agree on objectives. James and I were inspired by the towers, the bigger and more slender, the better. If the climbing sucked, oh well. For Honnold, in contrast, bagging the first ascent of a tower held no allure; he was more inspired by the quality of the climbs, and was particularly interested in finding good cracks. As Piero drove us through an area, we’d scope out climbs and haggle or vote on the finalists.

In this way we ended up one day sitting below a 100-foot-tall arch with a 180-degree rainbow offwidth crack splitting the underside of the formation. I had zero interest in climbing this heinous fissure, but Honnold was psyched. We didn’t have much in the way of wide gear, but the crack split the entire formation, and Kemple was able to solo an easier route to the top and drop a toprope down the crack from above. Piero’s helpers set up a table and chairs below the arch and I settled in to eat a sandwich and watch the show.

Ten feet off the ground, Honnold lunged for a basketball-sized hold that promptly exploded in his face, sending him winging across the arch. Once the route had spit him off, you could see in Honnold’s face that it was “game on.”

He jumped back on and for more than hour, battled his way up, across, and then down the other side of the offwidth. He shuffled across the horizontal section by hanging upside down by foot cams. “That was the most disgusting route of my life,” Honnold exclaimed, panting, his body covered in dust and bat piss, but with a huge grin on his face. He looked happier than I’d seen him all trip.

Piero’s Milan-based company, Spazi D’Avventura, had mentioned that Piero was a climber, but none of us ever bothered to ask him about his climbing background, though we did learn a lot about his many years leading tours in Africa during the four long days in the jeep. One day we were relaxing around camp, and Kemple was paging through a coffee-table book about Patagonia, written in Italian. “I’m in that book,” Piero mentioned casually, grabbing it from Tim. He passed it back open to a page about Cerro Torre and Casimiro Ferrari’s first attempt on the west face in 1970. Ferrari’s partner? None other than a youthful Piero Ravà. Piero had been a member of the famed Lecco Spiders, and back in the day had been a pioneering climber in the Dolomites and Patagonia, but was too modest to mention it earlier.

Since the beginning of the trip, Piero had been talking about a tower he called the Wine Bottle, and when we turned a corner and saw it for the first time, we all could see why. As the name implies, it was shaped like a bottle: fat down low, narrowing into a slender neck, and topped with a bulging spout. For once there was pretty much no discussion: everyone, even Honnold, took for granted that we had to climb it. The neck looked super sketchy, however: steep, loose, and distinctly lacking obvious weaknesses.

Pearson took us up an approach pitch that looked short and easy but ended up being a rope stretcher on bad rock with very little pro, a suitable warm-up for what was to come. When I joined him on the ledge, the expression on his face said it all: Your pitch is a friggin’ nightmare.

Sure enough, the neck of the Wine Bottle was about 60 feet tall, dead vertical, and covered with scaly protrusions. Too scared to free climb, I used a horrible hybrid style, partially weighting the bad gear to take some pressure off the fragile holds. About 25 feet above the ledge I arrived below two bizarrely shaped chickenheads. They were too big to clean off on top of myself, so I lassoed them with slings, clipped into my belay loop, and slowly eased my weight onto them.

Suddenly, both chicken heads blew, but instead of landing in a heap on top of Pearson, I remained hanging from one tiny chunk of sandstone that hadn’t blow with the rest. “Bolt kit!” I yelled down to James, who quickly sent up a hand drill. The bit quickly carved a hole so sloppy that when I tried to tighten down the bolt, it just fell out in my hand. Desperate now, I pounded two pitons into the crumbling hole. As the realization sunk in that even bolts could not protect me on the soft rock, I knew my gig was up.

I lowered to the belay and Pearson offered to have a go. With a toprope off the stacked pins, he free climbed to my high point, felt the moves above, then took a hang. The pins were holding body weight, but a fall was another matter.

Pearson bouldered up above the manky pins, twice returning to their dubious safe haven, then committed, climbing through to decent footholds a body length above. When he looked down at me, we both knew that he wouldn’t be downclimbing that section.

For the next 15 minutes he tinkered around, eventually placing a micro nut and cam. Both looked worthless, but Pearson seemed satisfied, and after another good shake he pushed up into a fingertip traverse out the overhanging bulge of the Wine Bottle’s spout. A good crack then led to the summit.

I followed the pitch like a bull in a china shop, pulling holds down around me. At one point, in a spot where Pearson couldn’t even consider falling, I simultaneously broke both footholds and one handhold and was left dangling from a crumbling chickenhead. All I could think of was thank god I backed off this lead—and if Pearson keeps this up, he ain’t gonna be long for this world.

Years ago, when I first found the Ennedi Desert on Google Earth, I’d been led to a photo journal from a French photographer’s trip there. There was a picture of a crazy formation, half tower and half arch, that you could say was the inspiration behind the whole trip. I’d passed this link along to the team, who found this formation equally inspiring, and Pearson had downloaded it onto his smart phone. We’d shown the picture to Piero, and he recognized it immediately: “Ahh, the Arch of Bashikele,” he replied with a knowing look and a long draw on his pipe. We kept asking him about it, and he kept giving evasive answers like, “Maybe definitely,” and, “We will see.” It became clear why he didn’t want to take us when he added, “You know there are vipers and cobras in camp there.” But the more he put us off, the more obsessed we became with climbing it.

He finally changed his mind after our knifepoint encounter below Aloba Arch. Arming ourselves had been a good call. Chin and I stared down the youths, and when they realized that these tourists weren’t going down without a fight, their leader gave us a long, hard look, then began backing away. Within seconds they vanished into the rocks.

When we arrived panting and breathless back at the jeeps to tell Piero, he just kept puffing away on his pipe, waving it off as no big deal. Apparently he’d seen a lot worse during his years in Chad, including once having his vehicle stolen at gunpoint. We were standing around, trying to decide where to go next, when someone once again threw out the possibility of the Arch of Bashikele. Piero scowled and puffed furiously on his pipe—but then suddenly the lines on his knitted brow relaxed and he replied: “OK, let’s go. But we can only stay there for one night.”

The drive took us through some of the roughest terrain we’d seen yet, with the jeeps driving up and over rocky ridges separated by deep ditches. But within two hours we turned a corner and there it was, the “Delicate Arch of the Ennedi,” as we preferred to call it. One look and it was clear that missing it would have been a tragedy.

It wasn’t really a tower or an arch, but rather both, or neither, and was quite simply the most bizarrely impossible rock formation I’d ever seen. Each leg of the arch featured a potential route, but the right-hand leg seemed to offer the line of least resistance to the summit, an easier slab pitch leading to a final steep headwall.

What transpired was much like our ascent of the Wine Bottle. Pearson took us to a poor belay below the crux, and I led on toward the summit, only to retreat from poor pins stacked in another botched bolt hole.

Pearson went up and spent the rest of the day climbing back and forth above my high point. When it started getting dark I suggested we bail and come back in the morning. I was actually pleased to find that Pearson had been impressed with the sketch factor.

That night in camp, we passed around a bottle of whiskey and watched the moon rise directly into the U-shaped gap beneath the arch. The Milky Way glowed more brightly than I’d ever seen it before. Surrounded by the immense desert, I got that feeling of being a tiny little speck of dust in this universe, but a happy little speck nonetheless.

We were hiking back to the climb before first light. Behind the tower, a dry riverbed snaked back into a box canyon, and as the sun came up I watched a little kid herd about 50 goats toward a grass patch on the outskirts of the canyon. I don’t think he knew I was there, but I watched his every move and it was fascinating to see his strategy for getting the goats down the little path.

Pearson had apparently made up his mind the night before that he was going to get the job done this morning, no matter what. At the highpoint he chalked up, yelled down for me to watch him, and set off up the final 15 feet of sandy rock between him and the summit. There was no further gear. I should have been terrified at my piece-of-junk belay, but I’d now climbed enough with Pearson to know that it would take an act of god for him to screw up and fall.

Ever so carefully he pieced it together, but at the lip, one move from the end, the holds disappeared entirely. Even Pearson couldn’t downclimb the section he’d just pulled, and he hung there for about five minutes calmly studying the problem. I think we both thanked his gritstone apprenticeship as he committed to a Houdini-style no-holds mantel onto the crumbling, flakey summit.

I had trailed a rope for Honnold, who quickly followed and joined us on the summit. Gazing off to the east, we could actually see the edge of the Ennedi, where the canyonlands ended and the Sahara desert began. Sand dunes stretched to a distant horizon somewhere off in Sudan, but in every other direction the desert was littered with countless unclimbed towers, buttes, and arches.